Filed under: Analysis, Anarchist Movement, Featured, Repression, The State, White Supremacy

“Disorder and crime are usually inextricably linked, in a kind of developmental sequence…”

– George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson, Broken Windows

“The policeman isn’t there to create disorder; the policeman is there to preserve disorder.”

– Richard Daley

Cover Image from Jason Cordova

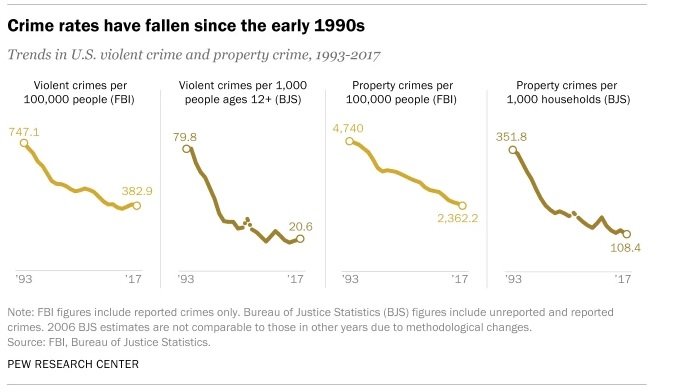

It may seem like a strange thing to say in today’s world, but crime is down and it has been falling for the last 25 years since it peaked in the early 1990s. According to the Pew Research Center, both FBI reports and annual surveys of American households both show that violent and property crimes have dropped severely since 1993:

Using the FBI numbers, the violent crime rate fell 49% between 1993 and 2017. Using the BJS data, the rate fell 74% during that span. Like the violent crime rate, the U.S. property crime rate today is far below its peak level. FBI data show that the rate fell by 50% between 1993 and 2017, while BJS reports a decline of 69% during that span.

But listening to “law and order” politicians like Donald Trump, one would have a hard time believing this, as Trump won the Presidency in part off of white fears of black “crime,” often hinting that he would send in the National Guard to Chicago if order was not restored. Far-Right and pro-Trump websites like Breitbart even included during the 2016 election cycle a section on their website entitled, “Black Crime.” This sentiment is also held by a sizable segment of the population:

But listening to “law and order” politicians like Donald Trump, one would have a hard time believing this, as Trump won the Presidency in part off of white fears of black “crime,” often hinting that he would send in the National Guard to Chicago if order was not restored. Far-Right and pro-Trump websites like Breitbart even included during the 2016 election cycle a section on their website entitled, “Black Crime.” This sentiment is also held by a sizable segment of the population:

In 18 of 22 Gallup surveys since 1993 that have asked about national crime, at least six-in-ten Americans said there was more crime in the U.S. compared with the year before…Pew Research Center surveys have found a similar pattern. In a survey in late 2016, 57% of registered voters said crime in the U.S. had gotten worse since 2008…

As we have shown, while fears of specifically violent and property crimes are largely misplaced, in reality, when politicians and the pundit class speak of crime, what they really are referring to is black insurgency. This in itself is not surprising, as following the Southern Strategy, Republicans looked for coded racial messaging in their campaigning. As Republican strategist Lee Atwater stated during an interview in 1981:

“You start out in 1954 by saying, ‘Nigger, nigger, nigger.’ By 1968 you can’t say ‘nigger’—that hurts you, backfires. So you say stuff like, uh, forced busing, states’ rights, and all that stuff, and you’re getting so abstract. Now, you’re talking about cutting taxes, and all these things you’re talking about are totally economic things and a byproduct of them is, blacks get hurt worse than whites.… ‘We want to cut this,’ is much more abstract than even the busing thing, uh, and a hell of a lot more abstract than ‘Nigger, nigger.'”

Flash forward to today, and images of black uprisings against the police are presented as the logical end result of black crime itself and Trump’s vow to send in the National Guard to Chicago was seen by his supporters as a preemptive measure against the next possible black uprising. After Ferguson, police also pushed a narrative of the “Ferguson effect,” arguing that crime was in fact rising in certain areas because police were afraid to come down hard on them in the wake of a massive uprising and media scrutiny. This view of the threat of black insurgency; one that lies outside of the gates of whiteness, is also reflected in the way that many people see crime in the US. As the Pew Research Center noted:

While perceptions of rising crime at the national level are common, fewer Americans tend to say crime is up when asked about the local level. In all 21 Gallup surveys that have included the question since 1996, no more than about half of Americans have said crime is up in their area compared with the year before.

Meaning, crime, insurgency, and the threat of it, was always something that was, over there; in danger of coming inside. If you want to hear this narrative in action, you need only turn on Fox News to hosts like Tucker Carlson. This reality is also reflected in the fact that communities that already are multi-racial and home to migrants and refugees, are less susceptible to xenophobic and racist smear campaigns, while those that view an unknown threat coming from far away, be it Black Lives Matter or MS-13, are not. Meaning, those putting the most stock on the potential threat of black and brown insurgency are communities that are largely removed from those populations.

But even in cities like Chicago, crime is largely concentrated in a small percentage of the cities population and within an incredibly tiny geographical area. As City Lab wrote:

In Chicago, a city often used in the media and elsewhere as an example of the worst of American urban violence, researchers found that a social network with only 6 percent of the city’s population accounted for 70 percent of nonfatal gunshot victimizations. Violent crime isn’t waiting to happen on any given block of a poorer neighborhood, nor is it likely to arise from just anyone who happens to live in one.

Meaning that everything from broken windows policing, to stop and frisk, to gang injunctions targeting broad areas of major cities, all largely have other goals in mind besides lowering crime – which they haven’t:

More than 30 years later, the evidence demonstrates that the broken windows paradigm does little to nothing to reduce serious crime but does tend to make people feel more unsafe, reduce trust in and cooperation with police, and could contribute to, in fact, producing and facilitating more violence.

The goal of these policies is clear: counter-insurgency. As the insurrectionary anarchist journal, A Murder of Crows wrote:

…following the upheavals of the 1960s and 1970s, the state switched to a strategy of permanent repression, or as he calls it, counter-insurgency. Learning from their past failures, the police developed a preemptive model of repression which sought to prevent insurgency before it happened.

Poor neighborhoods and districts, especially black and Latino ghettoes, which were the source of much insurgency during the 1960s and 1970s, are hit particularly hard by this preemptive strategy.

John Ehrlichman, one of Richard Nixon’s top aides, comments about the War on Drugs only further solidifies this point:

“The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying? We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin. And then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders. raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

…Coming Straight From the Underground

Beyond the fact that crime is dropping at the same time as police forces are militarizing and there are more Americans in prison, on probation and parole than any other country, other studies also point to the fact that policing even in itself does nothing to stop or hinder crime. In a famous study conducted in Kansas City in the early 1970s, it was found that when police stopped car patrols, the level of crime remained the same. This is to say nothing of the fact that most crimes are not reported to police, and those that are, largely are not solved.

The gang truce in the wake of the #NipseyHussle murder echos the historic gang truce in LA that was made just days before the LA Rebellion. Police and FBI responded by breaking up BBQs and arresting organizers. The 92 gang truce is still widely credited with reducing homicides. pic.twitter.com/sdtPkolPIk

— It's Going Down (@IGD_News) April 8, 2019

Moreover, when one looks at the history of revolt and we see times in which the exploited and excluded have come together and created both forms of autonomous power or attempted to mediate problems outside of the State – not only has crime drastically dropped, but moreover these formations are in turn attacked by the police. The reasoning is simple: autonomous forms of power threaten State authority. Here are some examples.

Before the LA Rebellion in the late spring of 1992 kicked off, gangs had come together to sign a historic gang truce which held throughout the rebellion and many years after it had ended. As Jeff Chang wrote in Can’t Stop Won’t Stop: A History of the Hip-Hop Generation:

By the time the Simi Valley jury delivered its verdict on April 29, 1992, in the trial of the four white officers who had beaten Rodney King, a gang truce had already been secured fifty miles away in the housing projects of Watts…But against all odds, the gang truce held in Watts and spread. In the weeks after the uprising, gang homicide tallies plunged, and stayed there.

Deputy Chief Matthew Hunt, the police commander of the South Los Angeles area, admitted to the Police Commission, “There’s no question the amount of violent crime has decreased [after the gang truces]. People in the community say they haven’t heard a shot fired in weeks. They are elated.”

Police were skeptical. “I’m concerned as to the true motives of the gang members as to why they would make peace,” one policeman said. “Is it so they can better fight with us, so they can better deal dope or so they can better be constructive in their neighborhoods? That would be the last item I would choose be-cause gang members have a thug mentality.”

But it had become clear to peacemakers that LAPD was out to disrupt and harass peace meetings and parties. At some events, cops appeared in large numbers without provoking an incident. At others, they forcibly broke up the meetings. In Compton, Congresswoman Waters and City Councilman Mark Ridley-Thomas came in person to intervene with police who were harassing gang members leaving a peace meeting. At Imperial Courts, police helicopters and riot squadrons swooped in to break up truce barbecues. When they did the same thing at Jordan Downs, residents and gang members sent thirty police officers to the hospital.

The LA gang truce between African-American and Latino gang formations held for years, and drastically dropped violent crime and the homicide rate in the LA area, even in the face of violent attempts by police to squash the movement and keep people from coming together.

Now, 25 years later, following the murder of hip-hop artist Nipsey Hussle, street formations are once against coming together and have called for a new truce. As one community organizer and gang member stated in The Guardian:

“We not fucking with the police … It’s a people’s movement.”

As another example, we can look towards the Occupy Oakland encampment that erupted in ‘The Town’ in the fall of 2011. As the Occupy Wall Street movement took shape, it quickly spread across the US, as people took to town squares and parks to occupy them with tents, encampments, soup kitchens, and communal make-shift cities. After the first few weeks of the encampment growing in Oakland, California, it was clear that the space was taking on a distinctly anti-state and anti-capitalist character. The general assembly agreed to not allow police into the area and refused to be co-opted by the local “progressive” city leaders who at first attempt to reach out to the sprawling commune growing daily outside of its own city hall.

The encampment also became a force of dual power, feeding hundreds of people per day, offering them a place to sleep, and providing various resources and mutual aid programs. While the camp itself was not without fights, strife, and internal conflict, even the Oakland police noted that crime fell while the commune was in control over the area now renamed, Oscar Grant Plaza.

But despite the fact that crime was dropping and the “Oakland Commune” was feeding and housing people, the police soon moved in against it, evicting it and almost killing several counter demonstrators in the process. Ironically, in doing so the police broke a massive variety of laws and ended up paying millions in damages, only to return the plaza to where it was before without the commune. As an article in Mask Magazine wrote:

Starting in the summer of 2013, the city began to pay out millions of dollars to those injured by police during the Occupy clashes. $1.7 million was doled out in a settlement with 12 protesters, some of which were injured in 2013. The settlement also forced Oakland police to adhere to their own rules on crowd control, which were constantly broken. In December 2013, $645,000 was paid to a man beaten by a police officer after the General Strike in 2011. Scott Olsen received $4.5 million in May of 2014. Then, in January 2015, it was announced that $1.3 million would go to people who were mass arrested on January 28th, 2012.

This trajectory played out again, when Occupy communards seized farm land north of Berkeley and took it over, creating a communal gardening area named, Occupy the Farm. Police responded with massive amounts of violence, arrests, and projectile weapons.

Everything you need to know about American democracy is at play in the police response to protests at #DeKalbCountyJail. The system is unwilling to enforce even its own standards + would rather use its resources to smash anyone demanding change rather than address basic concerns. pic.twitter.com/W1CAUNaaKg

— It's Going Down (@IGD_News) May 16, 2019

Lastly, when we look at the struggles of incarcerated people to end inter-gang violence or address systemic inhuman conditions, often the response from the State is outright brutality. This includes attacks on inmates in the SHU who participated in the Pelican Bay hunger strikes to end hostilities (racial gang violence), the sentencing to death of inmates involved in the multi-racial Lucasville uprising, attacks on members of the Free Alabama Movement (FAM) who organized protests against prison slavery, and brutality against recent demonstrations and protests in Atlanta against conditions at a local jail.

In all of these examples it should be pointed out, the police go out of their way to attack even legal forms of protest against the penal system’s inability to follow it’s own rules, while using forms of violence that the police themselves would deem illegal. Thus, through the state of exception; the State’s tendency to suspend the rule of law and level even deadly violence against the population, the police enforce a structural reality that refuses to abide by even its own rules but ensures social peace.

Exception of State

If it hasn’t been made clear by now, what the State is concerned about is putting down potential rebellion and revolt, not stopping crime. As studies have shown, policing in itself does little to actually stop or deter crime, but instead is more concerned with maintaining a material force that can put down the rabble. When one looks at the modern American police force which grew out of slave patrols, such a reality becomes much more logical.

With all this in mind, we first need to dismiss talk from the pundit and political classes about “crime” and things such as the War on Drugs for the smokescreens that they are. The State is not interested in making our lives better or more free; it is interested however in preserving, protecting, and expanding its own power.

We should also be on the look out for attempts by the State to attack and demonize organic subversive expressions of proletarian activity simply as criminal, even if in their makeup they include criminal elements. Examples of this include recent flash mobs by black youth in major cities, the outpouring of people in support of #DontMuteDC, as well as the growth of sideshow culture in various urban centers.

Ultimately, we need to build from just “signals of disorder” to gaining control of territory and building autonomy, outside and against State power.